Ancient sanctuaries were intricate and multifaceted sites that not only facilitated ritual practices but also served various social, political, and economic purposes. This principle also applies to the cult sites in ancient Cyprus, although these mechanisms have received comparatively little study here compared to ancient Greece, for instance. The new excavation campaign at the Frangissa sanctuary of Apollo has revealed a significant spatial and likely functional expansion phase during the Hellenistic period, shedding light on the dynamic processes of change and substantial structural interventions experienced by rural sanctuaries in Cyprus during this era. Further research into this complex presents immense potential, not only for enhancing our understanding of the site itself but also for Cypriot sanctuaries in general.

The initial excavation campaign in 2021, funded by Amricha, unveiled the first ancient building structures, confirming the localization of the Frangissa sanctuary, which was previously only based on survey data. The team from the Universities of Frankfurt and Kiel, led by Matthias Recke and Philipp Kobusch, deepened the exploration of these structures through the continuation of excavation activities and a 5‑week campaign in 2022. Once again, the work received financial and personnel support from Amricha, as well as funding from the ROOTS Cluster of Excellence at CAU Kiel.

Larger than expected — extent and structure of the sanctuary

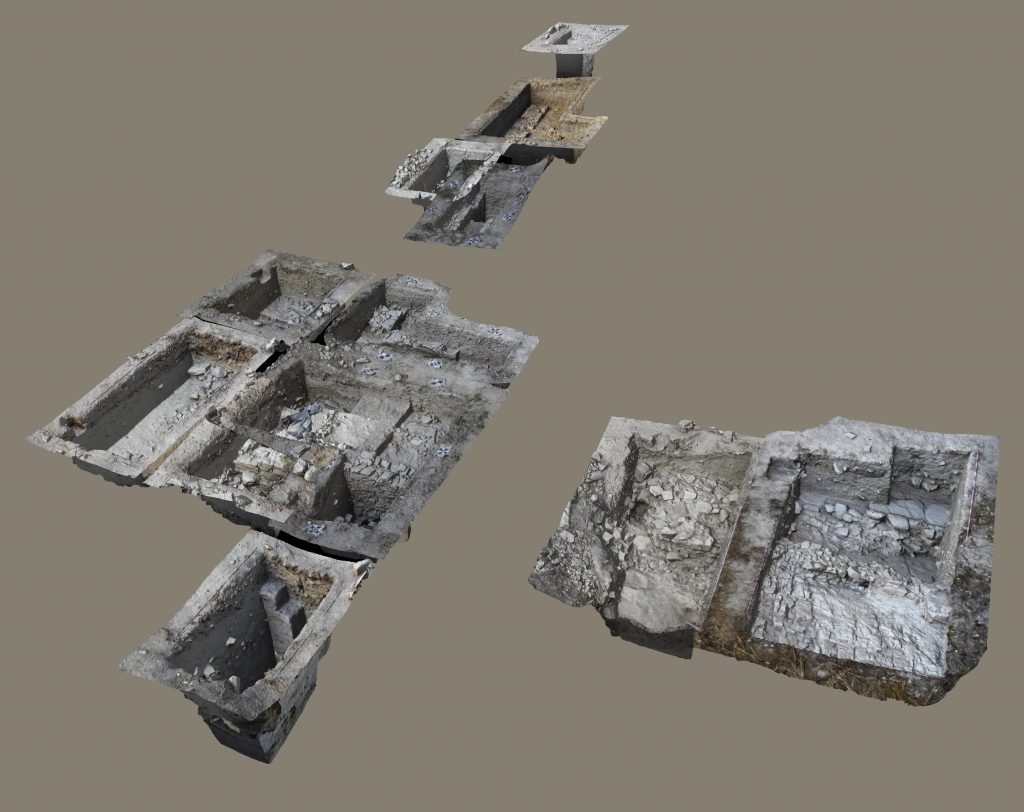

The recent excavations have significantly expanded our knowledge of the building discovered in 2021. The architectural enclosure of an open district, measuring at least 12 x 17 meters, has been revealed. The walls are meticulously constructed with carefully placed stone plinths, reaching heights of up to 1.20 meters. These plinths formed the base for mud-brick masonry, which is no longer preserved today. The area’s floor consisted of a meticulously prepared, flat rammed earth floor, partially preserved despite its fragile nature.

Based on current knowledge, this complex’s construction can be dated to the Hellenistic period. However, the district underwent successive alterations after its initial construction. In a later phase, short transverse walls were erected, possibly connected to a flat stone base that was built later and ran parallel to the enclosure walls. At the current stage of excavation, this stone base is likely interpreted as a support structure for pillars that carried the roof of a hall encircling all sides. This measure further diversified the potential uses of the courtyard, potentially serving to protect particularly valuable votive offerings from the weather.

Towards the end of the excavation, a stepped structure constructed from meticulously carved ashlars was discovered in the immediate vicinity of the courtyard area. These blocks, of considerable size and quality, were previously unknown at Frangissa. The precise trimming and use of imported materials make this finding exceptional. Typically, all architectural structures within the sanctuary are made of local limestone. The complete uncovering of this monument in a future campaign will greatly enhance our understanding of the sanctuary’s layout. The fact that this monument is located outside the newly excavated courtyard complex suggests that the area utilized within the context of the sanctuary was even more extensive.

Although the exact relationship between the Hellenistic courtyard and the old excavations, and consequently the main area of the sanctuary discovered in the 19th century, remains unclear at present, the rich finds, such as votive figures, impeccably prove its connection to the sanctuary. The core of the sanctuary, documented by Max Ohnefalsch-Richter in 1885, also consisted of an open courtyard but contained a roofed cult building within it. Based on the discovered artifacts, this part of the sanctuary can be traced back to archaic times. The newly found structures are the first evidence of a larger extension phase for the Frangissa sanctuary, significantly expanding the built-up area and potential uses during Hellenistic times. The Hellenistic sanctuary is now known to be more than twice as large as previously believed.

Small shards bring important insights

Furthermore, the discovery of seemingly inconspicuous terracotta fragments yielded a particularly remarkable result. These fragments belong to a larger-than-life male terracotta figure, similar to the renowned Colossus of Tamassos in the Cyprus Museum (which originates from the same sanctuary). Like its counterpart, this figure was assembled from several individual parts, and its robe exhibited intricate incised ornaments. Fragments with similar characteristics had been previously found in 1885 and taken to the museum in Nicosia. The newly discovered fragments align perfectly with these old fragments, securing the identification of the sanctuary with the site excavated in 1885, which had previously been based on numerous circumstantial pieces of evidence.

The planned continuation of the excavation in 2023 will focus on investigating the courtyard’s function, as little is currently known about the use of the inner open space. Additionally, the precise connection between this extension and the sanctuary’s core will be explored by locating the old excavation. Only then can we gain a better understanding of the sanctuary’s overall functioning and the interaction among its individual functional parts.

Hand of a limestone votive figure

Terracotta head of a chariot driver

Torso of a terracotta figure with beard and cap